Who decides where the boundaries between languages are drawn? And is your language ‘foreign’?

This piece was originally written for Demos Journal, and was first published here. It also features four terrifying hyperlinks.

Humans tend to throw up walls upon encountering ideas we don’t understand. Spectrums of experience are broken down into boxes; identities have their variations chiseled away until they become square-shaped pegs for square-shaped holes. Thus, with boundaries delineated for the categories we have made, we can file the unknown neatly away, and finally relax in the presence of a known quantity.

It should therefore come as no surprise to hear that the very tool used to define these categories – that of language – has also been broken down by humans with all the subtlety of a small rampaging child taking on a Tower of Babel made of alphabet blocks.

It is estimated that 6,500 languages are spoken in the world today, and within that number exist many more dialects, creoles, and regional varieties. Yet there is a certain futility in trying to organise

languages when one considers their slippery, ever-changing nature. Take Catalan, for example: is it a language or a dialect? And is your opinion on this affected by your definition of either of these terms, or is it swayed by your emotional connection to Barcelona? Besides, where can languages, dialects, or any other category of communication be said to begin or end, when the very existence of spoken words is based on thousands of years of cultural and linguistic interchange?

Despite the world’s languages sharing snippets of vocabulary, grammar, turns of phrase, and even onomatopoeia, they arguably remain defined and understood by their differences. Encountering a language one doesn’t understand is to run up against a brick barrier of communication: you can’t break through it, so you sort of stare mutely at it instead, feeling vaguely disconcerted. Indeed, the very term ‘foreign languages’ owes its existence to the notion that languages we don’t understand are ‘foreign’ – beyond the boundaries of our own experience. Through this propensity to ‘other’ that which we don’t understand, we end up shutting ourselves inside the little box of language which we have labelled as our own, be that ‘English’, ‘Australian English’, ‘Australian Public Service English’, or what have you.

It’s also worth questioning whether perception of the ‘foreign’ nature of other languages is amplified within the mindset of English speakers. As English enjoys its era as the world’s lingua franca (such irony that that expression literally refers to the “Frankish language”), and reliance on technology grows, native speakers of English can grow

complacent in language-learning. English and the West have become a

primary reference point for much of the world, and English-speakers

receive repeated affirmation that speaking English is somehow the norm, simply through seeing the majority of the world striving to learn our tongue. Subsequently, for all that we Australians hit the linguistic privilege jackpot merely by virtue of being born here, there is a flip-side: the need to interact with other cultures and languages is

repeatedly presented to us as non-essential. We don’t need to interact

with them; it’s them who interact with us. This is evident even at a worldwide university level, where English is becoming increasingly common as the preferred teaching language, and scholarships enabling study at Anglosphere universities remain ever-prestigious and sought after.

Yet the real losers in this situation will ultimately prove to be us, because while everyone else is out there learning a second, third, or

even tenth language – and gaining cultural intelligence to boot – we’ll

be retweeting articles about the wonders of translation technology. And while that technology may have many positive uses, it is unlikely to enable an individual to understand language and culture, entwined as they are, as well as somebody who has prioritised actual interaction

with a worldview outside of their own. In Europe, for example, or more mobile areas of South-East Asia, multilingualism is viewed as such a necessity that people just make it happen, whether through education systems or self-motivated study, and whether they enjoy it or not. Schools have compulsory classes in second or third languages, and students leap at the opportunities to study or work abroad, in part to improve their multilingual proficiency. Such skills are prioritised

because they are valued. Granted, we don’t see multilingualism as essential in part because of our geographic position: Australia, like many Anglophone nations, doesn’t border onto a non-English-speaking country. Indeed, Australia technically doesn’t border onto anything. Yet we are a large island in the Asia-Pacific – a region of enormous linguistic and cultural diversity, as well as potential – and from a cultural understanding perspective, we are currently a bit of an awkward friend. It’s regrettable for everybody.

Furthermore, redressing this problem is far from evident. The fields of language and cultural studies necessarily advocate engagement with others, and thus acceptance – precisely the sort of mentality worth fostering within wider Australian society. One might have hoped that the ANU, therefore, as a leading educational institution, would do its part in promoting the importance of language-learning in Australia with regard to regional relations. Making cuts to studies of language, history, and culture of the Asia-Pacific with the finesse of a villain in a slasher movie (see here, here, here, and here), however, is a curious response to this issue, and unlikely to engender a solution.

So we must hope that in spite of setbacks, individuals – if not all

institutions – will increase efforts to look outwards, and to embrace

diversity with respect to both culture and language. Such a mentality

would likely develop the framework through which one sees the world;

similarities would become every bit as visible as differences (though

both can exist and be acknowledged without one or the other consequently being invalidated).

On that note, to people who look beyond the horizons of their own country and linguistic sphere (such as the aforementioned polyglots who learn out of necessity) the concept of the foreign language is diminished in magnitude. It loses its mystery when faced with the understanding that apparent enigmas can be decoded. Its ‘foreign’ quality – and the intimidating aspect of this – shrinks in significance to anyone willing to seek out the points that different languages have in common.

It is therefore a shame that we cling with such vehemence to notions of difference, separation, and foreignness when discussing languages; after all, differences between what we define as languages are far from

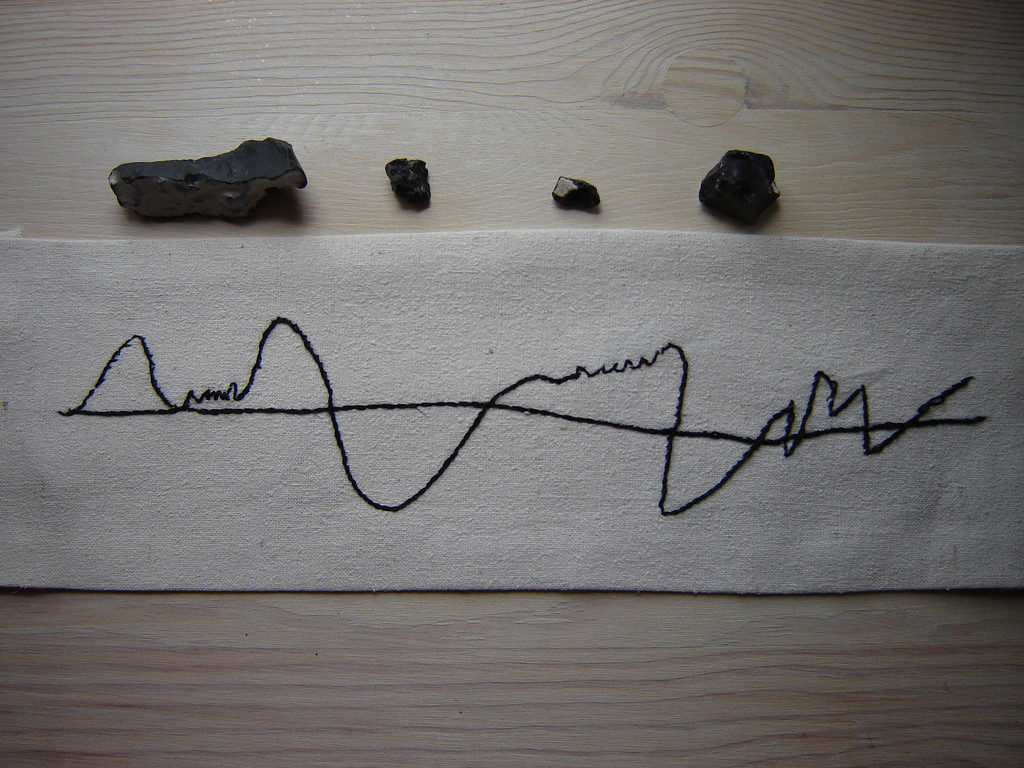

insurmountable. Indeed, rather than seeing languages as existing within separate boxes, or even within separate families (Romance, Germanic, and the like), perhaps it is time that we began to view them as existing in a perpetually developing state of interconnection. Maybe we should try adjusting the radio frequency before denouncing the words as unintelligible.

After all, the confines of language – along with language itself – are ultimately all inside our own heads.