Having come across one too many Byronic heroes loitering on hillsides, I decided to dissect a few in order to get to know them better. For the record, the use of ‘torturous’ in the title indicates a play on the word ‘tortuous’, rather than ignorance of its existence…!

(Originally written for Capital Letters (ACT Writers Centre), and accessible on their website here. Additionally, special thanks to Chloë M. for sounding board services – this piece is better thanks to your input).

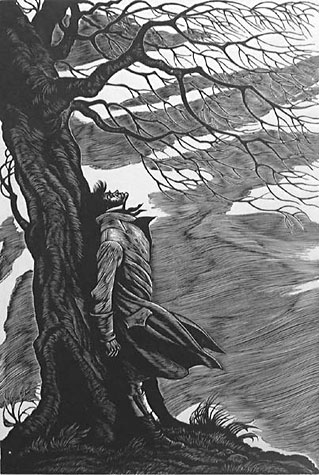

The concept of the ‘Byronic hero’, named after Romantic poet Lord Byron, has existed for over 200 years. With his square jaw, tortured soul, and propensity to loiter on desolate hillsides, the Byronic hero’s enduring presence in storytelling across many mediums has rendered him one of the most recognisable literary archetypes in fiction. Though more melancholic and despairing than the classic Romantic hero, he too is characterised by introspection, strong personal beliefs, intelligence, sophistication, and (more often than not) a dark and mysterious past: an angst-filled cocktail of characteristics which will likely be familiar to many readers. Yet what is the true nature of this enigmatic figure—and is it time he were left out in the cold?

Brooding Beginnings

Lord Byron was described by a lover of his, Lady Caroline Lamb, as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Having inspired a summary such as this, it may be unsurprising to learn that Byron’s first Byronic hero appeared in a semi-autobiographical poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, and was described by contemporary critic Lord Macauley as “a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his brow, and misery in his heart, a scorner of his kind, implacable in revenge, yet capable of deep and strong affection.”

This description of a Byronic hero remains accurate in discussions of the archetype today, for the character became recurrent in Byron’s writing and inspired numerous emulatory successors. This phenomenon has stretched well into modern times.

Here are some famous examples:

- Edmond Dantès (The Count of Monte Cristo)

- Heathcliff (Wuthering Heights)

- Edward Rochester (Jane Eyre)

- Dracula (Bram Stoker)

- Dorian Gray (The Picture of Dorian Gray)

- Erik / “The Phantom” (The Phantom of the Opera)

- Stephen Dedalus (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)

- Many characters in action films and superhero franchises (e.g.

Batman, Captain Jack Sparrow, Anakin Skywalker, James Bond, and various

Russell Crowe roles) - Tyler Durden (Fight Club)

- Severus Snape (Harry Potter)

- Edward Cullen (Twilight)

Looking at this list, one can spy a few trends. Firstly, Byronic heroes typically appear to be heterosexual male characters. Secondly, there is an inordinate number of supernatural beings amidst their ranks. Thirdly, many of them are pretty unpleasant people to be around—and this is especially worth noting, for it prompts the following question: what is behind the Byronic hero’s enduring popularity?

Humanity, Morality, Immortality

The longevity of the Byronic hero is due in large part to his audience’s ability to identify with him. He’s often unpleasant to the point of being rude and aggressive—these characters do a lot of ‘snarling’—but while he shows the potential to be a villain, he is generally portrayed with such empathy that he is consequentially humanised and endeared to readers. He has made mistakes, and is more riddled with filth than a blue cheese—yet we love him for it, because he embodies a very human form of vulnerability through his shortcomings. We can identify with him as a result of our own flaws and hidden shames, so it’s little wonder that he has become immortalised in our works of fiction.

Nevertheless, his appearance in popular modern forms, such as the obsessive Severus Snape and the psychopathic Edward Cullen, have sparked new debate on what it means for a character to be a Byronic hero. What does it say about us, that we are so drawn to these characters; and what effect might consumption of their stories have on our real-life attitudes?

(These questions can be addressed using gender-related frameworks—after all, where would the Byronic hero be without the attractive heterosexual female on hand to nurture the long-buried goodness of his tortured soul?)

Essentially, the Byronic hero is a figure of wish-fulfillment for men as well as for women (further evidenced by the fact that he is written by both, too). One can understand the appeal of the Byronic hero from the male perspective—and why an apparently difficult man like the “mad” and “dangerous” Lord Byron might have written himself into such a semi-autobiographical figure. The Byronic hero is typically powerful and fascinating. His peers (especially the attractive female ones) generally don’t point out when he’s sulking, but instead seek to understand his deeply individual, unjustly-maligned self. He can also treat those around him very badly and yet still be irresistible to women, like some ill-tempered Casanova who has miraculously learnt how to play the piano prodigiously in spite of his many hours pacing the moors. Bonus points if he’s a gifted poet.

From the female perspective, meanwhile, the appeal is also clear. Maybe we’re all power-hungry: similar to how the power of the Byronic hero can be attractive to men, the power a woman can have over the Byronic hero is undoubtedly appealing to female readers. The attractive female (often in need of saving too, let’s be honest) often develops into the Byronic hero’s greatest love and greatest weakness; this subsequently leads to her being the only person with the power to reform him, for he is willing to make great changes and sacrifices for her and her moral code.

Furthermore, the female character—often placed so as to be ‘inhabited’ by the reader—is usually the only girl (ever—or at least, excepting ‘tragic backstory’) to have captured the Byronic hero’s gaze / melted his heart / stayed his desire to rip out her jugular. That’s pretty flattering. The Byronic hero is therefore appealing to the girl living through the female character in a way in which a nicer, more emotionally-balanced man might not be; for this classic ‘bad boy’ is nice to that one girl, and her alone, because she is special and he can recognise that.

Yet it’s not difficult to spy problems with the Byronic hero as a concept, and the way in which this could negatively impact an audience’s mindset. After all, storytelling plays a large role in reinforcing cultural values and socialising people: its power over our attitudes is not to be underestimated.

For men, the Byronic hero is both an unattainable and unrealistic representation of an actual human being. This archetype could thus create misplaced feelings of inadequacy in audiences, while also portraying an undeniably negative behavioural model for healthy relationships (self-absorbed solitude is nobody’s right, and neither is the attention of an attractive female). Indeed, certain Byronic heroes, such as the oft-termed ‘romantic’ Heathcliff, can be said to feed into the culture of toxic masculinity—i.e. pressure on men to be ever more unemotional, sexually aggressive, etc., particularly in interactions with the opposite sex. Such a portrayal of masculinity harms both men and women.

Women, on the other hand, arguably also receive destructive messages via stories featuring Byronic heroes. Narratives about emotionally unavailable men who just need to be understood by the right woman can encourage women to enter into abusive relationships, whereupon they may they tolerate terrible mistreatment and emotional manipulation on the basis on wanting to ‘fix’ their real-life Byronic hero. The problem here is that Byronic heroes aren’t real: an actual flesh-and-blood person rarely turns from a raging jerk into a romantic Jesus. Nevertheless, the perpetuation of the fantasy of the Byronic hero directly impacts what women perceive as acceptable or not in relationships, and can subsequently render warped power dynamics in a relationship perceivable as the norm.

So what does this mean for writers?

You may be contemplating whether or not you should write a Byronic hero. Well, naturally you can write whatever you like; however, I would argue that the Byronic hero has reached his retirement age, and that he is a trope worth avoiding (unless one can portray him with a particularly original or critical spin). If you must employ this archetype in your writing, then at least show us what happens in his life after he gets the girl, or how he responds to electricity bills, or whether he ever carries the groceries in from the car. Something new—anything! What if he were romantically interested in men? Or had an obsession not with blondes, but with bonobos? Or perhaps he suffers a midlife crisis when forced to compromise his busy schedule of brooding to give guided tours of the British countryside?

In such a case—if one strives for originality—maybe he won’t end up being a Byronic hero at all. Yet when one thinks of the Byronic heroes we already have…

… is this truly such a loss?